This is my post for day 9 of the Inkhaven writing retreat.

Finding treasure at the British museum

I recently visited London for the first time. I didn’t have much free time to do sight-seeing, but if there one thing I was going to visit, it was the British museum. Among the tablets and tapestries, there was a gallery holding an exhibit on currency. The exhibit spanned everything from cowry shells to gold doubloons to Zimbabwean trillion dollar bills. But the item that caught me by surprise was a £50 note.

Not being from the UK, I wasn’t sure if this was a standard £50 note being displayed for comparison purposes or a special edition one. A quick google told me that it has been the standard issue note since 2021. It featured computer scientist Alan Turing. This was awesome to see. It reminded me of how the portrait on the US $100 note is not a former president, but instead scientist (and founding father) Benjamin Franklin. But what really struck me was what was beside Turing.

It was a table specifying a Turing machine.

Reader: I don’t know how to convey to you my excitement about this table of letters. Turing machines are practically a religious symbol for me. Seeing this symbol prominently featured on the largest-denomination note of such an important currency was like seeing my religion validated. And it wasn’t just the pretty graphical version; it was an actual table. I needed to get to the bottom of this.

Following the paper trail

I was leaving London soon, but I decided that I was willing to pay £50 for this very cool souvenir.

Being a normal, modern person, I had not actually had reason to acquire any physical British cash while in London. So I decided that I’d try to get a £50 note when I inevitably walked by the currency exchange desk at Heathrow airport. This worked fine, except that I had to get three £20s from the ATM and then exchange them for a £50 and a £10. I spent most of the £10 on airport snacks.

After I arrived home, I finally got around to looking up what the internet had to say about this design. Since I’m pretty familiar with Turing machines, the notation on the note did look familiar, and I had a pretty good guess that it was from the paper in which Turing first introduced his machines. (Of course, he didn’t name them after himself; he called them “automatic machines” or “a-machines”.) I can never quite remember the title of this paper, because the title is On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem. The word “Entscheidungsproblem” is German for “decision problem”, and Turing used the German word because of the profound influence of Hilbert’s program.

The Bank of England’s official website for this note says the following;

The design on the reverse of the note celebrates Alan Turing and his pioneering work with computers. It features:

- A mathematical table and formulae from Turing’s seminal 1936 paper “On Computable Numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem” Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society. This paper is widely recognised as being foundational for computer science.

- The Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) Pilot Machine which was developed at the National Physical Laboratory as the trial model of Turing’s pioneering ACE design. The ACE was one of the first electronic stored-program digital computers.

- Ticker tape depicting Alan Turing’s birth date (23 June 1912) in binary code.

- Technical drawings for the British Bombe, the machine specified by Turing and one of the primary tools used to break Enigma-enciphered messages during WWII.

- The flower-shaped red foil patch on the back of the note is based on the image of a sunflower head linked to Turing’s morphogenetic (study of patterns in nature) work in later life.

- A series of background images, depicting technical drawings from The ACE Progress Report.

Which is all lovely, but I notice that it does not actually say what the table means.

Looking through other search results, many people were talking about what this choice of portrait meant in relation to Turing’s former conviction for homosexuality and posthumous pardoning. Or they were joking about how only criminals use £50 notes. But there was essentially no one talking about the technical details.

The paper itself was easy to find, and from a quick visual skim I quickly found the table that matched the note.

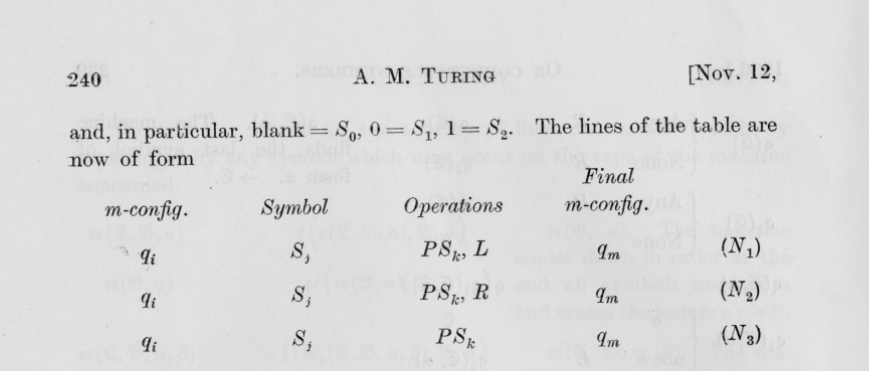

Since the sentence immediately before says “The lines of the table are now of the form”, I realized that this table does not specify a Turing machine, but instead just shows us how the rules of a Turing machine can take one of three forms.

Digression on how Turing machines actually work

I might as well take this moment to give you a quick description of how Turing machines are defined.

They are an extremely simplified abstract model of computation. The computing “machine” has a finite number of “internal” states, and can access an unlimited “external” memory in the form of one long tape. The tape is made of discrete cells. Canonically each cell holds either a zero or a one, but you could have a fancier tape if you wished. At any given time, the machine is in one of its states, and can read one cell of the tape. Each state is just a rule about what the machine will do next. An example rule looks like this;

if tape cell = 0

write 0 to the tape cell

move read head left

go to state 3

if tape cell = 1

write 0 to the tape cell

move read head right

go to state 2All the states are exactly like this, except they differ in what they write, which way they move, and what state they go to next. In the notation on the bank note, each q is a name for a state, each S is a name for a symbol of the tape, L means “move left” and R means “move right”. The last q number is the state we should go to next.

So the table is just saying that, according to this particular notation, there are three different types of rules: ones where you move left, ones where you move right, and ones where you don’t move at all. That’s why it’s not a specification of a particular Turing machine.

Under the table

But below the table, the note also has this line;

which is not immediately below the table in the paper. Instead, it’s in the middle of the next page.

This page is just showing how to convert between several different ways of notating a Turing machine, which are variously used in other parts of the paper. Earlier on the page it says “Let us find a description number for the machine I of §3.” So to find out what this specific machine does, let’s head back up to section 3.

But before we go there, since we now know roughly how this notation works, let’s try to reason it out for ourselves. Some Turing machines have behavior so complicated that the only way know what they’ll do is to run them. But sometimes you can eyeball the rules and see that it’s simple.

The first thing I noticed is that it’s specifying rules for four states, q1 through q4. The semicolons are separating the rules.

The second thing I notice is that the goto-states are also labeled q1 through q4, so this could conceivably be a complete Turing machine.

But the third thing I notice is that the read-symbol in all four rules is S0. That means the machine is underspecified; if we give it a tape with S1 on it, it will not have a rule for what to do.

The fourth thing I notice is that the move-symbol for all four states is R. That means that no matter what, the tape head is moving right. So this is basically a “print-only” machine.

Final answer

Putting these things together, we can conclude that, as long as we start the machine on a tape filled out with S0 in every cell, then it will just print something and keep moving right. But what will it print? Since there are a finite number of states, it must print something periodic. Now that we know the machine is very simple, we can confidently trace out the exact steps of the machine.

Assume we start in state q1 with a tape full of S0. State q1 prints S1 and then moves to state q2. State q2 prints S0 and moves to state q3. State q3 prints S2 and moves to state q4. (It looks like we have three tape symbols, so Turing opted for a slightly fancier tape in this example.) State q4 prints S0, and finally moves us back to state q1. So, dropping the S, the machine just prints this;

102010201020…

A little disappointing, but at least it’s well-defined, and not the most trivial possible Turing machine.

Now let’s check out work, and read what the paper says.

- Examples of computing machines.

I. A machine can be constructed to compute the sequence 010101….

Huh… well, we were close. We thought it was a machine that printed a pattern of period 4, but apparently it’s a machine that prints a pattern of period 2.

If you read through enough of the paper, you find out that Turing is deliberately putting in “spacers” between every printed cell as a sort of scratchpad cell, which is erased at the end of the computation. But this is just a trick that is very useful for an example machine later in the paper. It’s not essential for the definition of Turing machines. So I claim that our original guess is a more accurate description, and that the Turing machine on the bank note is one that prints 1020 repeatingly.

If you’re interested in understanding this paper more deeply, the book The Annotated Turing by Charles Petzold is a very gentle line-by-line journey through the entire paper, including much historical context. If you’re comfortable with any formal mathematics, the original paper itself is quite readable.

All this makes me wonder how exactly the Bank of England decided on this design. Presumably they paid a computer scientist to check that it made sense? Or maybe a historian who specialized in Turing and understood his paper? I think that a much cooler Turing machine choice was possible, but I understand prioritizing historical accuracy and simplicity over putting Easter egg puzzles on your currency. Overall, it was a satisfying micro-quest. Perhaps this souvenir will fit nicely between my Knuth check and my Bristol pounds.

Wait omg how’d you get a Knuth check? (I know generally how it happens, but I mean you specifically!)

LikeLike